Who was the first white man to set foot in Kentish? This intriguing question at this late date, is not likely to get a definitive answer. We can only speculate over a few possibilities based upon information gleaned from old historical records. Let’s work our way through three possibilities.

1790s – An Abandoned Sailor – Samuel Cox (alias Samuel Jervis)

The first European visitor to the Kentish district could have been a young abandoned seaman named Samuel Cox, who became the first white person ever to live in Van Diemen’s Land. His incredible story has been much written about in the early history of Northern Tasmania, though some doubt its veracity.

Just one year after the First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay and some 14 years before any Europeans settled in Van Diemen’s Land, the British ship Regent Fox became one of the earliest ships to make a whaling voyage into Australian waters. In 1789 it entered the Tamar River searching for fresh water. When the Captain sent a small row boat ashore to find water, one of the young crew members volunteering to go was the captain’s 16-year-old nephew Samuel Emmanuel Jervis from Leitchfield, England. He had become so afraid of his uncle that he made up his mind to abandon ship.

When Sammy was 10 years old, his father died, and the young boy passed into the care of his sea-faring uncle, Captain Jervis. Initially the Captain placed Sammy in a boarding school until he was old enough to go to sea. When the boy eventually joined the ship, crew members convinced young Sammy that his stern storm-hardened uncle was planning to cast him off on some remote island, so that once back in England he could claim the boy’s inheritance for himself. Young Sammy became so frightened he decided to abscond in Van Diemen’s Land rather than risk some tiny oceanic isle. As soon as the row boat reached the shore near the Tamar Heads, Sammy Jarvis bolted into the bush and hid until the Regent Fox was forced to leave without him.

Found by some aborigines near Port Dalrymple, Sammy after some initial fears, was accepted into their tribe and lived with them for the next 25 years.

Each summer, this Port Dalrymple tribe trekked inland to spend the warmer months under the Western Tiers and regularly visited the Toolumbunner ochre mine up the side of Mt Gog. Over these next 25 years (1789-1814) if Sammy just once climbed up Mt Gog to see what was over the top, or per chance his tribe was given permission by the local Tommeginne natives to hunt the big boomer kangaroos down on the Plains, then Sammy Cox must hold the honour of being the first European to set foot in Kentish.

In 1814, ten years after the first white settlement had been established at Tamar River, Sammy came across some white settlers at Carrick. He then left the aborigines and attached himself to the pioneering Cox family in the Carrick/Hadspen district, eventually adopting their surname.

It was the flour miller Thomas Monds who took an interest in Sammy and first wrote his story down. Today his incredible life is celebrated on the walls of the ‘Sammy Cox bistro/dining room’ in historic Carrick Inn at Carrick. First licenced in 1833, it is a regular dining spot for locals and groups. Sammy Cox ultimately died at a great age in the Benevolent Society Home in Launceston.

1820s – Absconders – E Hope & companion

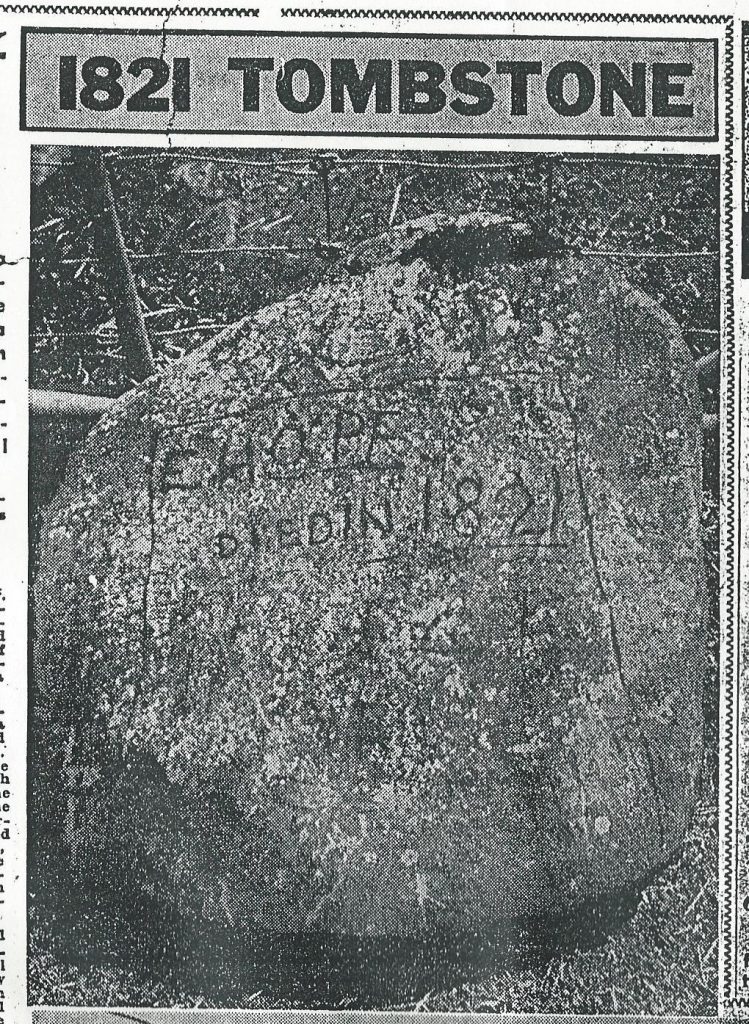

The second possibility is two absconders who apparently hid in the Kentish area in the very early days of the colony. In December 1963, Darrell Sharman of Sheffield was scrub-bashing across Lance Manning’s property on top of Vinegar Hill when he stumbled upon a small headstone half buried in the undergrowth. Cut or scratched into solid basalt, its inscription read E Hope died in 1821 and was propped against another stone, which also had an inscription, but was by then indecipherable. Sharman reported his find to the local Council office, where it was felt it must have come from escaped convicts. The local Health Inspector Roy Austin inspected the site and made some inquires in Hobart, but when convicts’ records didn’t yield anyone with the name E Hope, interest in this very unusual discovery waned, some concluding it must have been a hoax. Today nobody knows what happened to this stone.

In hindsight, this decision to abandon the significance of this unique discovery seems much too hasty. The date 1821 on the headstone fits in perfectly with the time period for escaping from the earliest settlements on the island. Some years after establishing the first settlement on the Tamar River, a severe shortage of food occurred when ships failed to arrive from England with further supplies. Eventually this famine became so extreme, Lieutenant Paterson was forced to release all assigned servants, convicts and military men to let them fend for themselves in the bush. Some soon discovered that with the possession of a gun and a dog, they could live independently and free. By1813 when the threat of any famine had ended, the number of absconders still living in isolated areas all over the island was estimated to be about 200 escapees. These absconders included men from ranks of military regiments and sailors escaping from various whaling boats.

This was same time as the bushranger Michael How emerged as the joint leader of a band of twenty-nine convict absconders and army deserters. Two years later he controlled a loose alliance of nearly 100 outlaws who came close to taking control of the whole island. Their alliance with ex-convict stock keepers, shepherds and hunters in remote areas meant they were always one step ahead of the law.

Michael How wrote defiant and threatening letters to Governor Davey in Hobart Town signing them Michael How, Lieutenant Governor of the Woods. Even though How was captured and killed in 1818, the problem of absconders existed to a lesser degree for a couple more decades.

The unexplored northern section of the island, west of Westbury, was a favourite place for absconders. Some made for the Rubicon River where they would try to board boats bound for the mainland that were forced to shelter in the river during storms. One escapee hid out on Avenue Plains at Parkham with stolen cattle, as did the bushranger Matthew Brady. On the slopes of the Western Tiers behind Jackey’s Marsh, the ruins of a mountain hut were found many years ago, along with a good sized iron pot and the skeleton of a European man. So, our two absconders E Hope & companion, who chose for their hide out, a location over the Mersey River and up the Dasher River to Vinegar Hill had the perfect place to live indefinitely without fear of being captured.

1830s Escaped Convict – Andrew “Scotty” M’Pherson

The final possibility was an escaped convict from the Penal Settlement at Macquarie Harbour on the West Coast. He was an educated military offender of fiery temperament named Andrew M’Pherson. After escaping and trekking his way north for some weeks, he eventually stumbled on to the Kentish Plains, which he called Scotia after his homeland. After passing over the Plains and across the Mersey River, he reached Westbury in the last extremity of destitution and exhaustion, where he surrendered to the acting Police Magistrate Henry Bonney.

M’Pherson’s story first appeared in the Launceston Examiner on 5 and 12 March 1887 and again by Mr H. Stuart Dove in the Examiner dated 10 June 1931. Dove wrote:

“Among the letters of the late Thomas Hainsworth there is an interesting reference to the first white man who set foot on what was afterwards known as Kentish Plains. The writer says that most people are under the impression that the Government surveyor N L Kentish was the discoverer of this important district when employed cutting a road 15 ft. wide from Elizabeth Town to Emu Bay. The real discoverer of the plains was an escaped convict from Macquarie Harbor, whose name was Andrew M’Pherson, but better known as “Scotty.” He named the district which he had found in the course of his wandering “Scotia” like a true patriot.

On arriving at Westbury, destitute and exhausted, he gave himself up to Henry Bonney, district constable of the western district, who afterwards became one of the first residents of Frogmore, Latrobe. M’Pherson was a man of education, a military offender, whose hot Gaelic blood had been the means of getting him into a series of troubles. M’Pherson wrote to Thomas Scott, then Deputy Surveyor-General, an account of his discovery, and through the intervention of that gentleman and Mr J. H.Wedge, he was pardoned.”

This story originated with Thomas Hainsworth (1832-1896) who lived at Sherwood Cottage, Sherwood near Latrobe. An amateur geologist, Hainsworth came from England in 1854, along with a boat load of Welsh miners to work at the Mersey Coal Fields at Tarleton. When the coal mines failed, Hainsworth took up teaching and became headmaster of several schools. He was a leading figure in the very early days of Latrobe, maintained an interest in the mining exploration of the Kentish district and was a regular correspondent to the Examiner newspaper. He was close friends with the historian James Fenton of Forth and Police Magistrate Henry Bonney, after the latter moved from Westbury and settled at Frogmore Latrobe, from whom he obviously heard about M’Pherson’s exploit.

Penal settlement on Sarah Island at Macquarie Harbour operated between 1822 and 1833. In the 11 years it existed, 112 convicts escaped from the prison on Sarah Island, 62 perished in the bush and nine were eaten by their comrades. Of the others, at least ten Macquarie Harbour escapees were captured or surrendered to the Van Diemen Land Company employees on reaching the North West Coast. One escapee gave himself up in the upper Leven River after having murdered his companion some time before.

Andrew M’Pherson’s escape must have taken place in the very early 1830s to coincide with Henry Bonney’s time at Westbury. If so, that puts M’Pherson’s epic journey after Captain Rolland and the VDL Co surveyors had explored this Mersey-Forth region. However, Andrew M’Pherson does appear to have done what all the earlier explorers failed to do – that is to be the first white person to walk across the Kentish Plains.

So as far the first Europeans to cross the Mersey River into our Kentish region, perhaps all three colourful characters can claim a tiny place in our emerging local history.